For many Americans, Memorial Day always brings to mind the iconic images of U.S. military cemeteries with row after row of stark white tombstones, and every grave decorated with a small American flag.

National cemeteries are laid out uniformly in various locations around the country. The Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) National Cemetery Administration maintains 155 national cemeteries in 42 states and Puerto Rico as well as 34 soldier’s lots and monument sites.

Some of these cemeteries had their beginnings during and immediately following the Civil War. Before the war, fallen soldiers were usually buried in a family plot or a local cemetery if they were lucky since there was no graves registration organization in the U.S. military at the time. Soldiers would simply be buried where they fell. Families would have to go find their loved one after learning of his death and then have to arrange to have the body shipped home, paying for all of the costs involved.

*** Please sign up for CBN Newsletters and download the CBN News app to ensure you keep receiving the latest news from a distinctly Christian perspective.***

For example, roughly 14,000 soldiers died from combat and disease during the Mexican-American War of 1846, but only 750 sets of remains were recovered and brought back, by covered wagon, to the U.S. for burial. None of the fallen soldiers were ever personally identified, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Union soldiers prepare to bury Confederates killed in the battle of Antietam, Maryland in September of 1862. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

White Skulls, Bones and Other Remains

During the Civil War, the armies were tasked with the collection, identification, notification of next of kin, and burial of their dead. And the burial of those killed in action was usually the job of the victor. But the generals in the armies were more concerned with defeating their enemy than decently burying their dead or the enemy’s dead.

Human remains on the Gaines Mill Battlefield in Virginia. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Soldiers were often reminded of what could be their fate when marching through an old battleground. They would see the gleaming white skulls, bones, and the other remains of their fallen comrades that had washed out of their hastily shallow-dug graves or had been rooted out by hogs or wild animals

Another view of unburied dead on the battlefield of Gaines Mill near Cold Harbor, Virginia. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Some soldiers never received a decent burial. With just some dirt thrown on top of them, many bodies were left to the elements. And their bones would create a horrifying scene for the living for years to come.

Lincoln’s Role in Honoring the Fallen

Then, on July 17, 1862, President Lincoln signed legislation authorizing the federal government to purchase ground for use as national cemeteries “for soldiers who shall have died in the service of the country.”

When Lincoln signed that 1862 law he was making a statement. Forevermore, the United States government would be responsible for its citizens who sacrificed their lives in service for their country. The government, not their families, would take care of their mortal remains and would see to it that they were perpetually honored for their service.

The first cemeteries were established near battlefields, including Mill Springs National Cemetery in Nancy, Kentucky; hospitals, including Keokuk, Iowa; and other troop concentration points such as Alexandria, Virginia, according to the National Park Service (NPS).

The Grafton National Cemetery in Grafton, West Virginia. The first national cemetery in West Virginia. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

After the three-day battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the bodies of 7,058 troops (3,155 Union, 3,903 Confederate) were left scattered in fields and farms surrounding the town. Burials began quickly as fears of epidemic rose. The dead of both sides were hastily buried in shallow graves on the battlefield, crudely identified by pencil writing on wooden boards. Rain and wind began eroding the impromptu graves, and Gettysburg’s citizens called for the creation of a soldiers’ cemetery for the proper burial of the Union dead, according to the NPS.

The state of Pennsylvania purchased the property for the new cemetery and the reburials began on October 27, 1863. They were completed by November 19, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln was invited to the cemetery’s dedication. According to the American Battlefield Trust, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony at the Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery to honor the fallen and reassert the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address:

“The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced,” he said.

But the cemetery at Gettysburg was only for Union soldiers. In 1873, the remains of Confederate soldiers killed at Gettysburg would later be recovered and sent to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond as well as cemeteries in Raleigh, Savannah, and Charleston not because of the U.S. Army, but because of the Wake County Ladies Memorial Association in North Carolina.

The War with More American Military Deaths Than All Other Wars Combined, Until Vietnam

In April of 1865, the Civil War ended. Today, it is estimated the war claimed somewhere between 620,000 to 750,000 soldiers, along with an undetermined number of civilians. It remains the deadliest conflict in American history. The Civil War accounted for more American military deaths than all other wars combined until the Vietnam War.

As author Drew Gilpin Faust notes in her book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War:

“Americans had to identify—find, invent, create—the means and mechanisms to manage more than half a million dead: their deaths, their bodies, their loss. How they accomplished this task reshaped their individual lives—and deaths—at the same time that it redefined their nation and their culture. The work of death was Civil War America’s most fundamental and most demanding undertaking.”

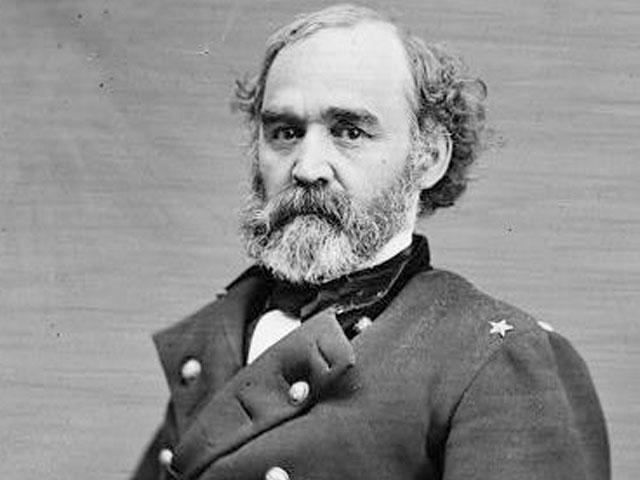

After the war, the federal government gave the task of finding, identifying, collecting, and reburying the Union dead to Brevet Major General Montgomery C. Meigs, the Union’s quartermaster general. He was one of the men who had transformed Arlington, Robert E. Lee’s former mansion, and turned it into a national cemetery during the war. (But that’s another story.)

Brevet Major General Montgomery C. Meigs. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Meigs took his job seriously and assigned U.S. Burial Corps teams to scour the old battlefields across the South, the Trans-Mississippi, and the most western battlefields for the remains of Union soldiers. These teams attempted to find, identify if possible, ship, and rebury the remains in the original 14 national cemeteries.

The re-interment process took a total of five years and resulted in establishing 50 more cemeteries to hold a quarter-million remains. The new cemeteries were surrounded by brick walls with gates that would not allow foraging animals to disturb the bivouac of the dead.

It was not until 1906 that congressional legislation approved marking their graves with headstones. Nearly half of the Union dead buried in national cemeteries have “UNKNOWN” inscribed on their tombstones because they could not be identified.

Tombstone of an Unknown U.S. Soldier marked with the grave number 1857 in the Shiloh National Cemetery, Shiloh, TN. (Photo by The Silverdalex/Unsplash)

As was the case at Gettysburg, the Confederate dead were left to the charity of their fellow Southerners, because they could not be buried in national cemeteries. According to the National Park Service, when the reburial corps in the late 1860s found the remains of Confederate soldiers lying near those of Union soldiers, they removed the Union soldiers but left the Confederates’ bodies.

Because identification of remains was difficult at best, some Confederate soldiers were reburied in national cemeteries, unintentionally as Union soldiers. Confederate prisoners of war were often interred in “Confederate sections” within the national cemeteries.

Private organizations, especially women’s organizations across the South, assumed most of the responsibility for Confederate reburials.

The Chattanooga National Cemetery in Chattanooga, TN. (Photo by Chris Madden/Unsplash)

Eight years after the war ended, Congress opened national cemeteries to all honorably discharged veterans of the Union forces. Legislation after World War I opened them to American veterans of all wartime service. Finally, after World War II, Congress expanded eligibility for burial to all veterans of U.S. armed forces, American war veterans of allied armed forces, and veterans’ spouses and dependent children.

Today, veterans of every conflict in which the U.S. participated — from the Revolutionary War to the Gulf — are buried in the VA’s national cemeteries. In addition to providing a gravesite, the VA provides a headstone or marker and perpetually cares for the grave at no cost to the veteran’s family or heirs. And yes, even Confederate graves are eligible to receive a tombstone under a federal law passed in 1929.

Watch “The Creation of National Cemeteries: The Civil War in Four Minutes” by The American Battlefield Trust

The remainder of this article is available in its entirety at CBN